Michael Cimino is as in love with himself as he is with his process, and Heaven’s Gate is a detailed technical schematic of the fragile ego of a filmmaker who got lucky once. There have been other examples of monumental failure. Spielberg’s 1941. Coppola’s One from the Heart. De Palma’s Bonfire of the Vanities. The Johnson County Range War was a subject near and dear to Cimino’s heart. Scion of an immigrant family himself, he perhaps wanted to tell the story in such an unglamorous way (with sweaty piles of Hollywood cash) and to then photograph those ugly circumstances with such beauty, he might’ve convinced himself he was making the greatest movie of all time. It’s easy for filmmakers to feel that way, particularly after such a stinging success as The Deer Hunter. His precious words and visuals deserved epic treatment. Indeed we’re not even thrust into the actual story until some 20 minutes have passed.

Make no mistake. This is a gorgeous movie to look at, especially in high definition. The Criterion disc offers a much cleaner visual as opposed to the atrocious MGM/UA VHS and DVD releases. A beardless Kris Kristofferson smirks at his friend, John Hurt’s valedictorian speech at the Harvard commencement ceremony. These well-dressed men are off to settle and tame a relatively young land. Kristofferson is headed to Wyoming, where he will become a local law enforcer. What was the point of these opening scenes? They’re beautifully-composed and choreographed images, but they do nothing for the movie, except to serve as a preamble to the violent, bloody madness that would erupt in Johnson County, Wyoming.

The Harvard prologue was part of the condition that Cimino manages to edit the film down to a viewable length. If Cimino could keep his movie under four hours, he would be permitted to shoot the prologue. I don’t understand this. I’ll make the movie shorter if I can add additional scenes? Twenty years later, immigrants are having a rough go at life in Wyoming. Being forced to trudge along in the dust and dirt Joad family-style, they’re met with bigotry and violent prejudice everywhere they go. This is a Holocaust story but it takes place on our land. Homesteaders are being systematically slaughtered by a group of thugs employed by the Stock Growers Association, and Kristofferson has to get to the bottom of it.

The Stock Growers are essentially the rich white man of Wyoming, hob-knobbing over cigars and whiskey, bitching about all the money they’re losing because of the immigrants. They draw up a “death list” of 125 names and commission hitmen (among them, Christopher Walken’s Nate Champion) to scrag the immigrants. Only Kristofferson’s old friend, John Hurt, has misgivings about the plan, but crooked baron Canton, played by Sam Waterston (this is a sensational cast) has the support of the Governor and the Commander-in-Chief. Cimino plays fast and loose with some of the facts, but he’s making a movie, not scripting a historical document.

With a little bit of judicious editing, the movie could’ve started right there with the “death list” without sacrificing Cimino’s narrative. Simple enough, cut-and-dried storytelling, but Cimino wants sufficiently photogenic clouds to pass over, sometimes holding up his well-paid cast and crew for days to get those shots. Cimino wants huge, billowing clouds of dust and mud-covered faces in the huddled masses of these outcasts. Cimino loves ambiance. The Deer Hunter was a movie made up of a majority of ambiance with a scattering of story about Robert De Niro in a Pennsylvania coal community before and after his experiences in Vietnam. Audiences would demand to know what the big deal is; why should we care?

It is an ugly footnote in American history, but Cimino wants you to be cast under his spell of imagery and attention to detail. Legend has it he ordered an entire standing street set to be torn down because it wasn’t big enough for his camera and large army of extras. It’s sad to note that most of these shots could be replicated nowadays inside a computer, but they would lack the clarity and depth of a filmed image. I’ve spent years trying to unravel the threaded-knot of mistakes connected with the production of the movie. Final Cut, Steven Bach’s memoir of the production, does a good job of finding the first few worms in the can.

The principal culprit of this most-famous of celluloid mistakes is United Artists, a studio that made quick and easy profits with low-to-medium budget movies for 50 years up to that point. Cimino’s script had been making the rounds for nearly ten years but westerns were pretty much dead by that point (thanks to The Missouri Breaks ironically produced by United Artists in 1976), and nobody was going to spend 10 million dollars on a western. Cimino’s early benefactor, Clint Eastwood, allowed him a shot at directing his script for Thunderbolt and Lightfoot starring Eastwood and break-out star Jeff Bridges (who also appears in Heaven’s Gate). The movie was well-received, and Bridges earned an Academy Award nomination.

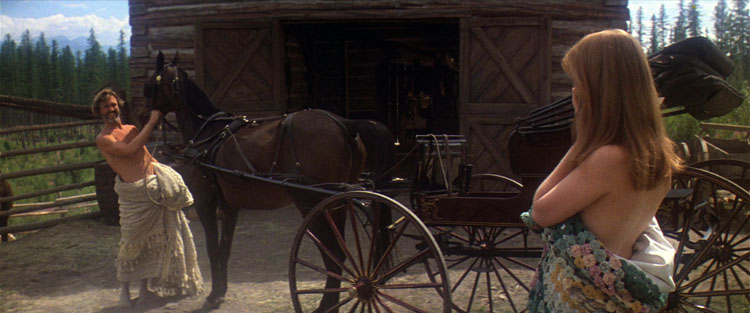

We’re over an hour into the movie before we get to Isabelle Huppert. While undeniably a beautiful woman (with a great deal of skin on showcase for the movie), she is indecipherable. She speaks with such a heavy French accent, I required subtitles to understand her, and because she is trying to speak English, her French compatriots would have difficulty as well. I can’t hate her, though. Something about her eyes and expressive nature reminds me of my wife, even if she has (as one executive described it) a “face like a potato.”

It’s obvious to me Kristofferson’s Jim Averill is slumming it, shacking up (in a forbidden fruit angle) with a brothel madam and, in a way, abusing her affections until there’s nothing left to abuse. Maybe I’m reading too much into their relationship, but Cimino is hell-bound to twist the very real lives of very real pioneers into a sadistic and wholly fictitious marionette. One of the bigger problems of the movie is the over-abundance of atmosphere. Cimino wants to show the audience the day-to-day lives of people who lived 90 years before. That includes whoring, dancing, cockfights, and roller skating.

The script is decidedly unbalanced. Actors Brad Dourif, Jeff Bridges, and Christopher Walken appear and disappear throughout the movie, and we aren’t sure of their motivations or even their reason for being in the story. There seems to be a love triangle between Kristofferson, Huppert, and Walken, but I can’t figure it out. One moment, Walken is a violent psychopath. The next, he is sympathetic and vulnerable. The second hour of the movie drags because Cimino shoe-horns his characterizations into the story. Also confusing matters is the moral ambiguity. The Stock Growers’ murderous actions are motivated by the fear that their resources are being drained by the influx of homesteaders. This is still a timely subject in 2019, and it’s easy to understand why there was panic, but Cimino doesn’t make a case for either side, except to say killing is wrong. We didn’t need a three-hour movie to tell us that.

The “range war” portion of the story doesn’t occur until roughly three hours into the movie and then continues until the end. The actors had fun for a time, at least until Cimino demanded more and more takes, but he thrived in an era when film directors had real creative power. The problem was Cimino didn’t have enough clout to escape the bad press that dogged the production’s steps. All movies get a share of bad press, but the boardroom contempt behind the scenes and Cimino’s obvious public antipathy for the people who controlled the purse-strings caused word to leak all through Hollywood, which served to destroy the reputations of not only the director, but his producer, and United Artists. In a way, there was a concerted effort to destroy United Artists. Hollywood practices a “zero-sum game,” wherein any studio’s loss is another studio’s gain.

It would be easy to put the blame for the failure of Heaven’s Gate on Michael Cimino’s shoulders if the movie was terrible. But it wasn’t. No matter what film critics of the time said. Canby’s clever “forced four-hour walking tour of one’s own living room” comment or Ebert’s “$36 million thrown to the winds,” notwithstanding, both of those film critics would know the enormous difficulties of making movies, yet presume to sit in on judgment of a piece of art neither of them ever intended to enjoy. Heaven’s Gate is a beautiful movie, in more ways than one. Exquisitely photographed and composed with excellent performances, production design, sound, and sound effects, the movie deserved an audience. It did no worse than what any other film tried to do. It dared to entertain.

David Lawler and John Froelich discuss Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate.