“Nothing’s riding on this except the first amendment to the Constitution, freedom of the press, and maybe the future of the country.”

All the President’s Men, 1976 (Robert Redford, Dustin Hoffman) Warner Bros.

“I was trained, and in those days, journalists were actually trained, and we were taught things like OBJECTIVITY and the need to be TRUTHFUL, and the need to be FACTUAL, and the need to separate FACT from OPINION. Would you believe such a thing?”

Melanie Phillips

Journalist, The Times

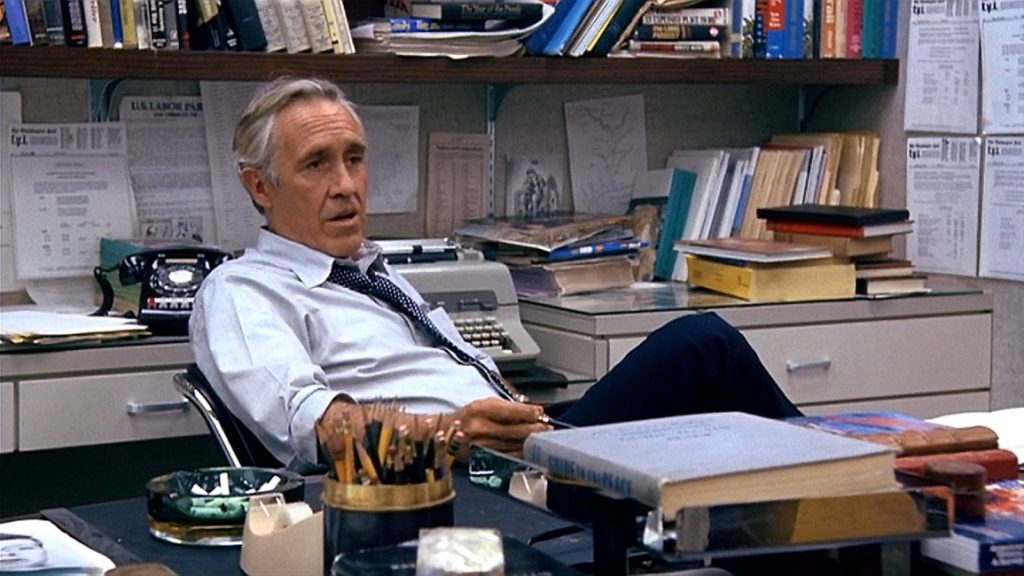

I studied Journalism in high school. I wasn’t very good at it, because I had a tendency to drift away from the facts and create my own adventures. I was going through a Hunter S. Thompson phase. As much as I failed in the realm of facts, I succeeded in courses such as Exposition and Imagination. I barely passed. To my 16-year-old self, Journalism was boring. It was just the facts. “A four-alarm fire broke out in Cheltenham last night. Three firefighters and one policeman were sent to the hospital with minor burns and smoke inhalation.” That’s Journalism. In practice, I can’t do it, but I can watch movies about journalists and All the President’s Men is the absolute be all-end all of the practice of journalism and journalistic integrity, as personified in Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee (Oscar™-winner Jason Robards).

The narrative push-pull of All the President’s Men exists as a triangle of sharp corners: the need to sell papers, the tease of a sensational story, and the observance of authenticity. Conservative reporter Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) is teamed with slovenly Leftist Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) to break the first stories of the Watergate Hotel break-in which occurred on the night of June 17, 1972. At first glance, it doesn’t look like much until Woodward places a call to his anonymous White House contact (Hal Holbrook) who tells him to “follow the money.”

This wasn’t an open-and-shut case; as in all good journalism, sometimes a whole new set of facts and theories will blossom from a simple line of inquiry. These days, you’d call it the “rabbit hole,” but in 1972 it was a job. The “rabbit hole” is given a visual identification through the various cocktail napkins, backs of matchbooks, and slips of paper Bernstein has collected in his various interviews. This is Bernstein’s “filing” system. When referring to an interview, he looks at the back of a matchbook. Bernstein and Woodward make for an interesting “odd couple.” Woodward sleeps in a tiny, messy apartment, but his demeanor is tidy. Bernstein has a well-kept living space, but he wears unlaundered shirts and looks like a slob.

That’s all we need to know about our two heroes. Even the incredible screenplay by William Goldman attacks the story from a journalistic standpoint. The movie is almost completely dispassionate and chooses to focus on the investigation and reporting. The faces we see are blank, non-descriptive; intuiting (with the exception of Jane Alexander’s Judy Miller, bookkeeper for the Committee to Re-elect the President) a non-judgmental and unemotional pretense. This was a hallmark of director Alan J. Pakula’s work in the ’70s through the ’90s.

How does one parse the facts? We collect statements. We interview. We do follow-up interviews, but most importantly, we name our sources. We don’t have to expose their names. We can make up a name, here or there, but we get the source. This is what mattered most to Bradlee – the back-up. The name that no one can dispute. This is when the fact becomes the truth. It doesn’t matter that the break-in will be, ultimately, connected to a sitting President – that truth becomes supplanted into the very active American conscience. That truth becomes personal, and it transforms into a decision you make when you choose to vote. It reminds me of Woodward’s John Belushi exposé, Wired, which was pure journalism through-and-through, and because of that, Belushi’s friends, collaborators, and family were galled at the dispassionate view of his life and exploits.

The newspaper’s job is to give you uncorrupted, unmolested facts. It is not anyone else’s right or obligation to distort the truth to conform to bias. When a preponderance of information makes it more than obvious impropriety was afoot in the President’s ambition to be re-elected, the name comes out and the connections are made. All the President’s Men is not a complete story. It ends long before Nixon’s resignation in 1974, but it was this early detective work that yielded the fruit of political corruption, and it brings to light many troubling thoughts. Chief among them: is it possible to maintain a dispassionate view with facts when money and the notion of power changes hands?