The Empire Strikes Back, 1980 (Mark Hamill/Carrie Fisher/Harrison Ford) 20th Century Fox/Lucasfilm

“You said you wanted to be around when I made a mistake, well, this could be it, sweetheart.”

First impressions. Early summer, 1980. Three years after the first Star Wars (which we still referred to as Star Wars and not “A New Hope,” whatever that is), the second movie in the cycle was released. Back to first impressions. Remember that this is a movie now lauded as a classic, as a masterpiece; the greatest Star Wars movie ever made, which it most certainly was, but we weren’t thinking about masterpieces. We were thinking about being pleased as members of the audience.

The Empire Strikes Back was not terribly popular among Star Wars fans at the time of release. I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking that I’m revising history to justify a narrative I’ve built up for my review, but no—this is the truth—it was not as popular as either Star Wars or Jedi. The numbers bear it out as well. While the sequel was released in more theaters, it made less money than the first Star Wars movie. The reasoning is simple: the movie is a downer, filled with reversal, setbacks, and failures. Our heroes lose. Han Solo is frozen in carbonite and Luke loses a hand.

This is what I wrote in an article for Film Threat a while back: “At its core, Empire has an indie heart and sensibility. Lucas, as well as screenwriters [Leigh] Brackett and [Lawrence] Kasdan, are never afraid to deal the characters we’ve come to know and love a crappy hand: the pesky hyperdrive, Luke’s injuries, the failed battle of Hoth, the alarmingly high mortality rate among the Empire’s finest officers at the hands of a pissed-off Sith Lord, the Empire’s takeover of Cloud City, Lando’s betrayal of Han, Han’s torture, Han frozen in carbonite, the failed rescue attempt, and so on. We can identify with characters that are brought to this level. In Star Wars, they are mythic superheroes, defeating their enemies against incredible odds. Here they are human beings up against insurmountable odds because the danger is real. They screw up miserably and their mistakes cause as much trouble for themselves as for the Empire.”

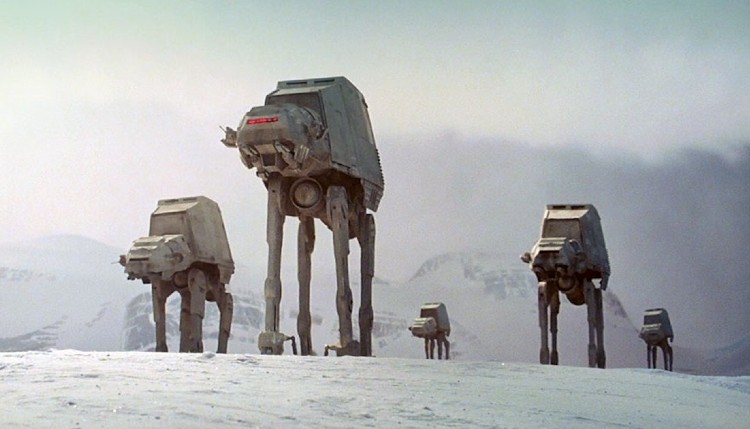

The destruction of the Death Star was a minor setback for the Empire. Vader went off to join the fleet and search for another Rebel base, this time on Hoth. The Empire destroys the base in short order (with the help of marvelous AT-ATs) and Han, Leia, and company evacuate while Luke goes off to find the great Jedi Master, Yoda. Luke’s training is interrupted after he sees visions of a future where Han and Leia are tortured by the Empire, so he decides to leave (against Yoda’s advice—this I’ve never understood) and tries to rescue them.

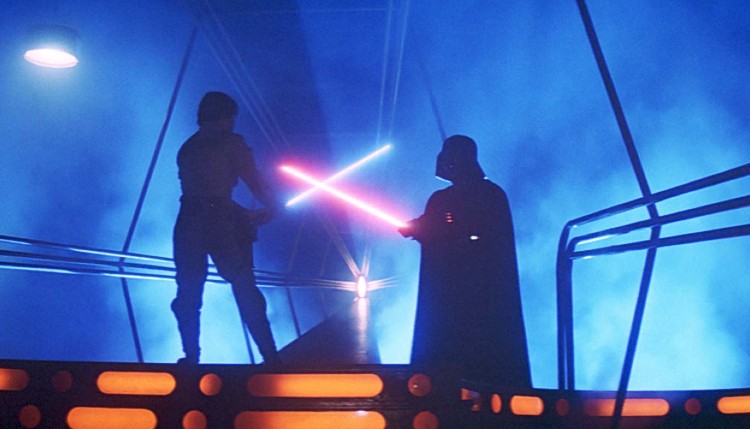

Even though he had the foresight to know what would happen to Han and Leia, he never suspects that he is being led into a trap. Vader attempts to seduce Luke to join the dark side of the Force, but his mojo doesn’t work so Luke decides to kill himself. He is rescued by Leia, and they crawl back to Rebel territory with their respective tails between their legs. The movie ends on a downer note. It doesn’t please the crowd; therefore, it wasn’t going to be as popular in those early years, and even on video a couple of years later you had to get past Empire to watch Jedi.

Going forward decades, at least moving into the ’90s when Randall made the statement in Clerks—“Empire had the better ending. I mean, Luke gets his hand cut off, finds out Vader’s his father, Han gets frozen and taken away by Boba Fett. It ends on such a down note. I mean, that’s what life is, a series of down endings. All Jedi had was a bunch of Muppets.”—this was when Empire began to take on exalted status. Empire did indeed have it all.