“I have no impulse to set the record straight. Why should I? Eighty percent of what people believe about my dad is just a projection of what they want to believe. It’s a Hollywood movie – very complex lives reduced to two hours – so how can it possibly show the depths of truth?”

ROSEANNE CASH

The Guardian

February 5, 2006

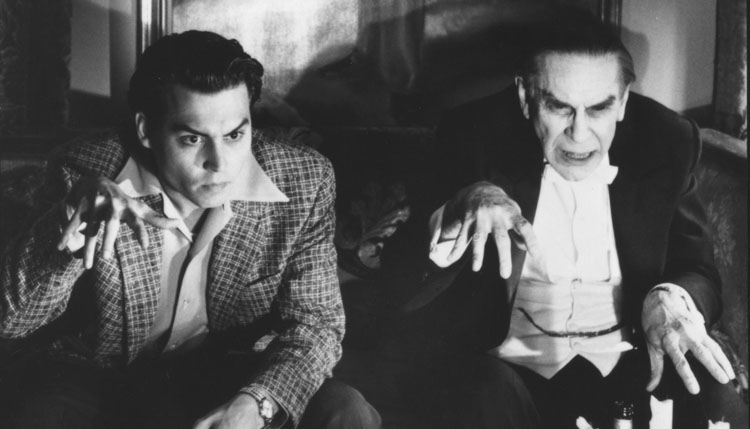

“This is the one. This is the one I’ll be remembered for.” Edward D. Wood, Jr. might’ve uttered those words at some point during either Plan 9’s three-and-a-half week shoot or premiere, but I doubt the latter. The movie did not have a proper premiere because, by the time the reels were locked, Wood had already sold back his interest in the movie (legend has it for a dollar) to his primary investors and was left worse than destitute. Tim Burton and writers Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski don’t want us to dwell on that fact. They don’t want us to contemplate Wood’s last days in the back-room of friend Peter Coe’s apartment because he and his wife, Kathy had been evicted from a dilapidated flop on Yucca Avenue in Hollywood. What they want is to elevate Wood to mythic status, by resting a story on his dreams and marginalizing his ultimate failure. Along the way, they pepper the story with interesting fictions such as Bela Lugosi’s hatred for Boris Karloff. In reality, Lugosi and Karloff were good friends.

In reality, Lugosi had a wife (his fourth) and child, yet we never see them in the movie. Why? Because it would detract from the fantasy of Ed Wood lifting his lonely friend out of obscurity and back into the limelight. In reality, Glen or Glenda did good business for George Weiss and Screen Classics (and Weiss never threatened to kill Wood), but Karaszewski and Alexander are telling a story of heroes going against the grain, not ne’er-do-wells with narrow hopes clinging to their livelihoods. Life is populated with enough ne’er-do-wells. Why should we have to buy a ticket and watch a movie about us? Ed Wood is a fantastic piece of fiction, but it is not truth. Where Ed Wood chronicles a famous failure, The Disaster Artist memoir by Greg Sestero and Tom Bissell seeks to capture the ambition of Tommy Wiseau, a filmmaker who displayed no discernible talent for filmmaking.

Sestero even has to make up bizarre fictions based on his observations of Wiseau’s temperament. Wood had no money, but an unlimited imagination. Wiseau had unlimited money, but no imagination. If Burton admires Wood, James Franco detests Tommy Wiseau. In the book, Sestero (a marginally capable actor) casts himself as the Elite consumed in the shadow of a bad filmmaker. Yet, the bad filmmaker surrounds himself with “professionals” who engage him in shouting matches and temper tantrums and then walk out on paying gigs because they don’t approve of his process. In 2019, Wood and Wiseau are immortalized for their guile while many of their professional collaborators are all but forgotten. As for the movie version of The Disaster Artist, it wasn’t necessary. The point of the movie seems to be the lying Hollywood Establishment laughing at someone who dares to play by his own rules. The Establishment pretends to respect Wiseau, but in reality, they are consumed with hate for him. The book is all we need, and frankly, I’ve seen far worse movies (professionally-made Hollywood Establishment movies) than either The Room or Plan 9 from Outer Space.

Enough about failure. Let’s talk about success. Bohemian Rhapsody seeks to turn Freddie Mercury into a god. This is supposed to be a movie about the rock band Queen, but instead, we get a VH-1 dramatized Behind the Music biography about Freddie Mercury with 17 different camera angles devoted to 5-minute dialogue scenes. The coverage is spectacular, but the rules of the filmed biography require a creative peak with which to chronicle a significant denouement. Ed Wood and The Disaster Artist end with the grand, glorious premieres of movies. Oliver Stone’s The Doors ends with Jim Morrison’s recording session for the song, “L.A. Woman,” while we get some text explaining that Jim died of heart failure and his wife Pam would join him three years later. A fitting epilogue for a bloated corpse of a movie.

Bohemian Rhapsody ends with Queen’s 1985 Live Aid Performance at Wembley Stadium in London. The movie would have you believe Bob Geldof’s charity concerts would never have succeeded if not for Queen’s (and more importantly, Mercury’s) participation. That’s right! Up yours, Madonna, U2, David Bowie. Sting, Phil Collins, Paul McCartney, Tom Petty, The Cars, Duran Duran, Mick Jagger, and Eric Clapton! There are too many discrepancies between real life and the fiction of Bohemian Rhapsody to get into, but again this is supposed to be fantasy thus Roseanne Cash’s statement about her father, Johnny Cash’s biopic, Walk the Line, remains. People will believe what they want to believe. Even if it isn’t true. Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood completely rewrite history for comedic and entertaining effect. Tarantino views our shared history as a series of fairy tales, rich in hyperbole and exaggeration, told with differing perspectives.

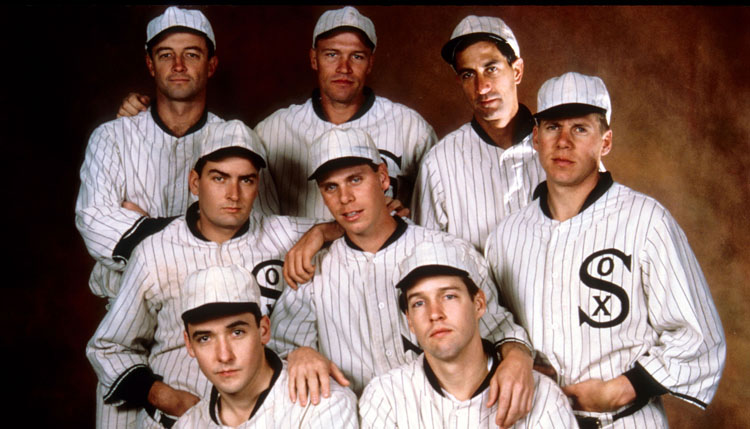

These inaccuracies are not limited to musical biographies. Historical epics are given the same treatment, particularly these days because of revisionism and perceptions of injustice. 12 Years a Slave suffered from inaccuracies in part due to Benjamin Northrop’s own uncertain remembrances and jumbled anecdotes from his memoir in addition to changes made by John Ridley for the script. While scholars have attested to the movie’s authenticity, they’re still making educated guesses based on their own personal (subjective) interpretations of the sourced material. Other movies, such as 2019’s Harriet offer a revisionist deconstruction of a wish-fulfillment fantasy based on a real-life character. Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate completely re-writes the motivations of real people and exaggerates incidents for dramatic effect. John Sayles’ Eight Men Out took more than a few liberties with the true story of the Chicago “Black Sox” World Series scandal of 1919 because the movie tells the story from the perspective of writer Eliot Asinof’s book, putting the blame on the club owners instead of the guilty parties.

Some movies, like Titanic, will take a very real incident and place fictional characters inside the action. This is a plain-faced and honest way to remind the audience that a movie is a work of fiction. The movie may have moments of authenticity, but it remains artifice. Titanic works as a complete and nearly-perfect movie experience because it surrenders to fantasy, and it doesn’t pretend to be anything else. Titanic did manage to offend the Scots with its depiction of Whitestar Line First Officer Will Murdoch who is shown in the movie shooting several passengers who scramble to get to lifeboats before killing himself. James Cameron was forced to apologize on the DVD commentary for his fiction. Fox apologized to Murdoch’s family and provided a “donation” to a charity in Murdoch’s name. The incident could have been avoided if some names were changed or a new character created, yet it does not change the fact that movies (all movies) are works of fiction.

The rubrics of movie-making demand a streamlined story and a time-tested formula. There must be good guys, and there must be bad guys. An obstacle must be overcome, and a victory (either real or cathartic) must be experienced. This is no way to learn about history, and I do remember a high school field trip to the movies to see Glory (1989), based on not one but two books about a regiment of Black soldiers during the Civil War. Glory is a fine film but also rife with inaccuracies. I suspect the point of the movie is not to educate but to inspire audiences. Steven Spielberg’s The Post took enormous liberties with the truth even down to the title of the movie. It was The New York Times, not The Washington Post, that first published Daniel Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers, but our pop culture of late requires females to play a more prominent role in movies (think of it as a form of affirmative action), and because The Washington Post picked up the Ellsberg story at some point later in the timeline (with Meryl Streep portraying Post publisher Katharine Graham), history had to be re-written.

“Very complex lives reduced to two hours.” A movie is a movie. The truth is something else. Movies are designed to entertain, not educate. In a useful way, movies reflect the culture and keep the history alive by giving audiences reference points in order to better understand choices and motivations. In a not-so-useful way, audiences believe movies and see them as true visual extensions of history with no embellishment, or as a way to further an agenda or talking point. Now more than ever, movies (and television shows) serve as a form of propaganda, political or social; this is why audiences get irate over something so painfully innocuous as Joker, an enthralling comic book product that had a legitimate purpose to entertain. A movie’s purpose is to entertain, not educate.