On August 15, 1979, 16-year-old James Dallas Egbert III left his dorm room at Michigan State University and disappeared. Feared kidnapped or dead, the efforts to locate the precocious genius lasted a month before he was inexplicably found 1000 miles away in a Louisiana coastal town few have heard of. During this time, his vanishing became a national story, was the source of endless media speculation which invented a national moral panic lasting a decade over a game sold at hobby shops which was weaved into a larger mythology said to involve the devil himself. Egbert’s tragic story inspired a sensationalized novel and subsequent TV movie adaptation airing in 1982, with this fictionalized narrative often conflated with or remembered instead of the more mundane version of events that really happened. This is the story of Mazes and Monsters.

Broadcast as a December CBS Tuesday Night Movie, Mazes and Monsters was itself an oddball, forgettable TV movie in the vein of many ‘based on a true story’ TV melodramas that had come before. (“Don’t run away, kids, you’ll end up like Dawn.” “Don’t do drugs, kids, you’ll end up like Richie.”) The two most interesting things about it were its production and sponsorship by household goods manufacturer Proctor & Gamble (themselves the victim of their very own moral panic at the time) and the fact that it was a heavily fictionalized interpretation of a real-life event that had played out about three years earlier. First, it’s important to get straight just what did happen in late summer 1979 that inspired all this, a story wildly misrepresented by the media which ended up focusing on a single aspect of the case that turned out to be an investigatory dead end.

The Story of Dallas Egbert

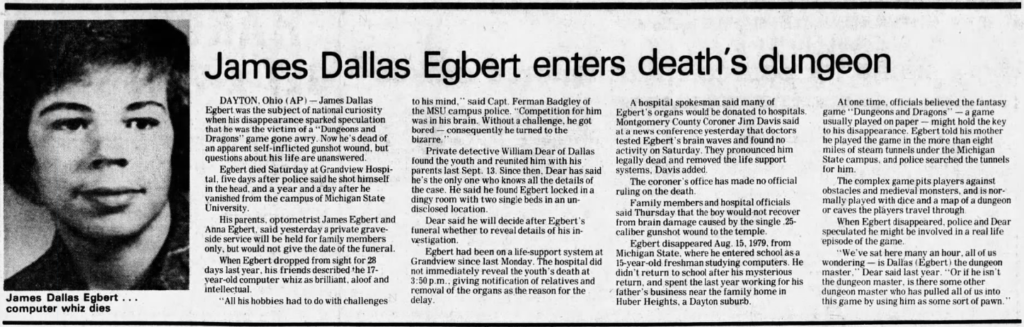

Called ‘Dallas’ by those that knew him, Egbert was a 16-year-old scholastically advanced MSU student from Dayton, Ohio with a reported 145 IQ majoring in computer science, about to enter his junior year. He was involved in sci-fi and fantasy fandom, read Vonnegut and Asimov, attended conventions and meetings of the campus Tolkien Fellowship and Science Fiction Society…all still largely considered oddball, fringe activities in the late 70s.

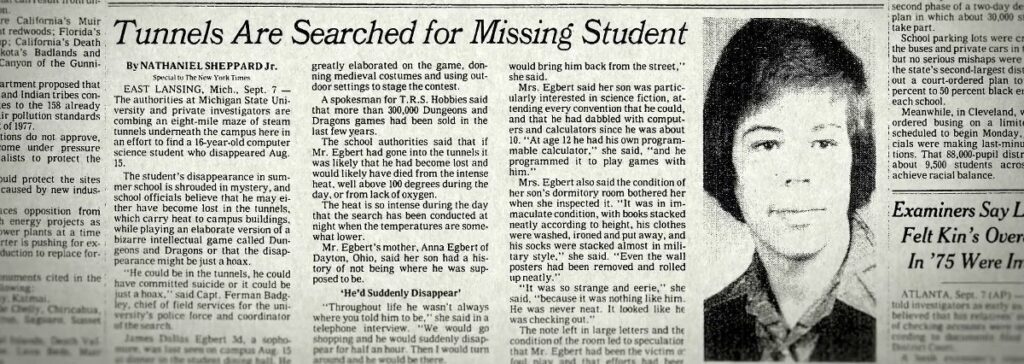

One Wednesday (August 15) he had lunch with a close friend in the Case Hall cafeteria, after which he was not seen for several days. Exactly what day he ended up being reported as missing to campus police is unclear, but it was either the following Monday or Tuesday. His roommate Mark (living off-campus for the summer) was the one who noticed he was gone and reported it. On August 22, one week after he was last seen, his parents and uncle hired flamboyant Texas PI William Dear to find him.

From the parents, Bill Dear learned about his fantasy/sci-fi interests, his scholastic precociousness, and his computer aptitude. However, one of the very first things his advance investigation team discovered was something left out or unknown to the parents. Dallas was also gay. He was even a member of the MSU Gay Council, a campus activist group. One of the major investigatory angles pursued was in fact Dallas’ gay acquaintances and hangouts, made problematic due to the fact that he was underage, which discouraged people from talking about any sex life he may have had. Bill Dear also found that Dallas enjoyed Dungeons & Dragons, a fantasy role-playing game from TSR gaining popularity at the time.

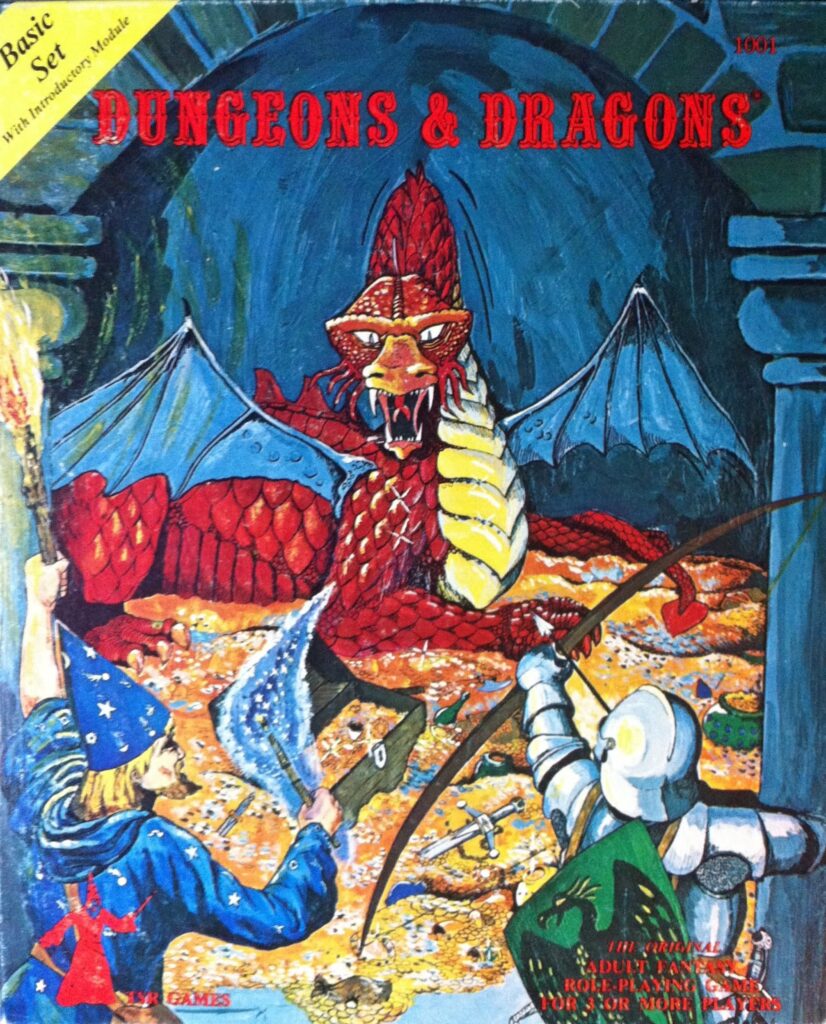

For the uninitiated, Dungeons & Dragons (or D&D, as it is often called) was first released in 1974 by creators Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson. It is a tabletop game derived from miniature wargaming, where players move model warriors, artillery, and vehicles across a mapped battlefield. In D&D, players create their own characters in a fantasy world of magic, monsters, and mythic quests. Gameplay usually involves player characters banding together in a campaign (continuing storyline) supervised by a dungeon master (a combination game supervisor and participant). Polyhedral dice are used to resolve in-game events and pencil and paper is used to keep scores. Player characters can thus accumulate experience points over multiple sessions of gameplay, which can lead to ‘leveling up,’ or becoming increasingly powerful. Popularity of D&D increased after the Basic Set was released in 1977 (many of us recall the box with the red dragon, wizard, and knight on the front), and exploded when the set was revised in 1981. You may recall Elliott wanting to play D&D with his brother and friends in E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial in 1982. And the game enjoyed an animated Saturday morning adaptation on CBS starting in 1983.

Bill Dear also discovered more disturbing things about Dallas – with his knowledge of chemistry, he was manufacturing and self-medicating with PCP and other drugs and that he was prone to suicidal ideation. According to two sources, university students were known to ‘LARP’ D&D (live action role play) in the 8.5 miles of utility corridors (AKA ‘steam tunnels’) under the campus. MSU was hesitant to give permission for these to be searched, claiming they were locked and inaccessible.

With other investigatory angles at a dead end, Dear played up the only angle that he felt still held out potential: the possibility that something had happened to him playing D&D in the steam tunnels. The intent was to pressure the university to allow an official, thorough search of them, which was still being withheld. “We’ve sat here many an hour, all of us wondering – is Dallas the dungeon master…or if he isn’t the dungeon master, is there some other dungeon master who has pulled all of us into this game by using him as some sort of pawn.” 1

After that press conference, media coverage exploded nationwide, focusing on the angle that his disappearance was related to playing Dungeons & Dragons. Preposterous media reports followed, which was the first time many people ever heard of D&D. Headlines such as “Fantasy Game May Have Claimed Missing Genius” ran across the country. Articles referred to it as a “bizarre” game enjoyed by “secretive” and “cultish” players, enabling the public to envision some kind of nightmarish, occult renaissance fair instead of a dorm room tabletop session involving beer, pizza, and Doritos.

To make a long story short, Dallas was finally located. Facing a great deal of academic and parental pressure, as well as feeling he would never be able to come out to his family, Dallas had attempted suicide. When that failed, he hid out with older gay friends, then took a bus to Louisiana and took a job as an oil field worker. D&D had nothing to do with his disappearance, however, secrecy about where he was during this time continued to fuel the D&D/steam tunnel narrative in media coverage. A year later he succeeded in taking his own life.

In subsequent months, novelist and Cosmopolitan writer Rona Jaffe hastily churned out her 11th book clearly intended to be based on the Dallas Egbert case. Born to an affluent Jewish family from Brooklyn, Jaffe often wrote about city life and relationships from a woman’s perspective. Her first novel about a group of twentysomething women working in publishing and living in low-end apartments while trying to make it in an expensive New York City was sold to 20th Century Fox for adaptation into the 1959 film The Best of Everything. Jaffe’s articles for Cosmo tackled city life with a ‘sex and the single girl’ attitude. More than a few critics have noted Darren Star’s Sex and the City plays like an updated version of Jaffe’s stories.

Jaffe, still receiving press coverage over her last novel, Class Reunion (1979), had been paying attention to the media coverage in the wake of Dallas Egbert’s suicide. By April of 1981, the fall release of her next book Mazes and Monsters was in the works. The book would be a thriller and something of a departure from her normal subject matter, this time writing about things she had no prior experience with. “When I heard about ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ and that people were spending 12 hours a week playing a game in which they kill monsters, using magic and violence, well, it was one of the freakiest things I had ever heard of in my life.” 2

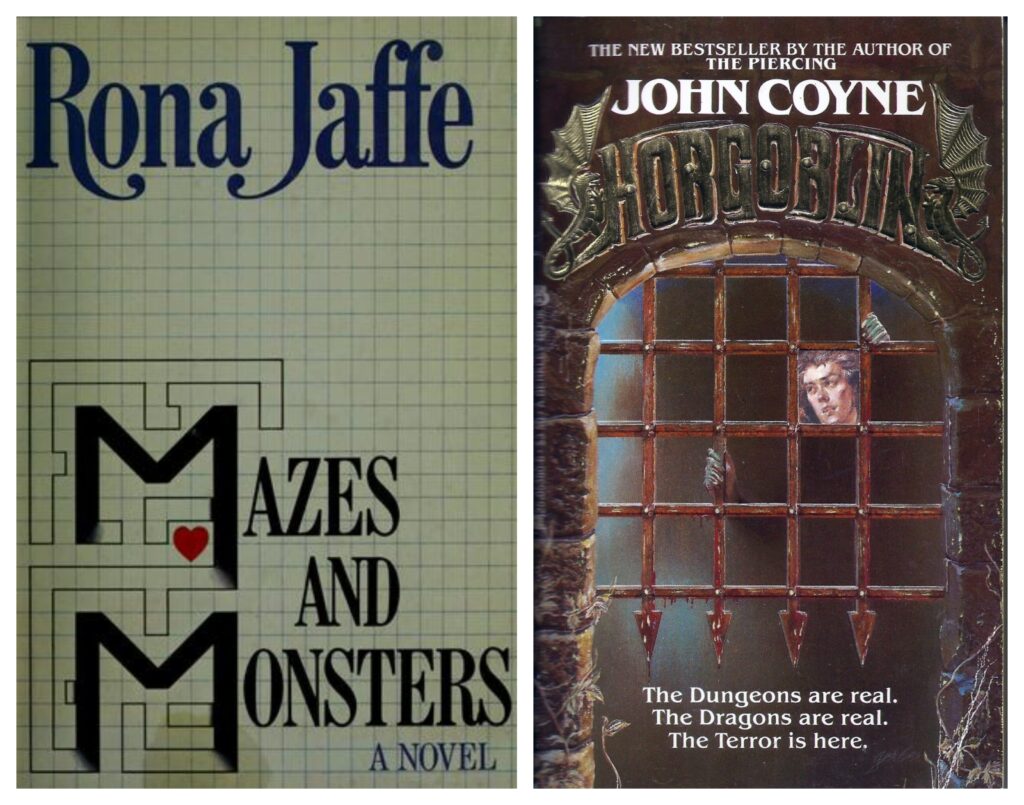

Jaffe took what must have been a crash course in playing D&D, then devised her own copycat game for her book, which became its title. By several accounts, Mazes and Monsters was churned out in mere days. Jaffe (or her publisher Delacorte Press) was in a rush to get the novel published, fearing another book capitalizing on Dallas Egbert media sensationalism might beat them to press. She was right. John Coyne was writing the now virtually forgotten Hobgoblin for Putnam, which was released November 25, 1981. The tagline for Hobgoblin read “The Dungeons are real. The Dragons are real. The Terror is here.” Coyne’s book featured a suicidal high school student addicted to a fantasy role playing game who has issues distinguishing between reality and fantasy. Coyne denies his novel had anything to do with the Egbert case. Mazes and Monsters beat Hobgoblin to press by two months. But even before it was released, CBS had already optioned it for adaptation into a TV movie, which would not air until December 1982.

1982 TV Movie Adaptation

The telefilm opens to a ‘live on the scene’ trenchcoated reporter doing a story on a college student that went missing, being searched for in some caves in upstate New York. Based on a police detective’s input, the disappearance is being linked to the fantasy role-playing game Mazes and Monsters.

We then get opening credits with a sappy love song clearly intended to drive away any kids that would have been remotely interested in watching. Introducing the characters six months before the opening scene, it is clear that writer Rona Jaffe simply took Dallas Egbert’s traits and split them among the various characters in her story, with herself serving as inspiration for female lead Kate.

The school term at Grant University is about to begin. The well-off JayJay arrives home to his high-rise New York apartment to find his mother has redecorated his room to a blinding white antiseptic look. JayJay has a 190 IQ, which the script points out, and likes to wear bizarre hats, drives a motorbike, and has a talking myna bird named Merlin (he was evidently a viewer of The Brady Kids). The intelligent Kate wants to be a writer, complaining to her mother about the chauvinist males she attends school with. The buff and blonde Daniel (hiding his athletic buffitude under preppy sweaters) just wants to write computer games, while his overbearing parents pressure him to attend MIT to study computer science instead of the local state U.

The connection between these three is revealed when they arrive at Grant, worried about finding a fourth player for Mazes and Monsters, the tabletop game they enjoy. Someone who won’t ‘flunk out or freak out’ like last year. Enter Robbie being driven up to Grant by bickering, overbearing parents who warn him ‘no more games.’ Robbie’s mother ‘could have been someone’ and drinks to get through the day. Robbie sees JayJay’s post on the bulletin board for a fourth M&M player but informs JayJay he ‘used to play.’

Attending JayJay’s party, he is talked into being their fourth player anyway, in no small part by Kate, who he is clearly attracted to. Later, with Daniel as Maze Controller, they begin an M&M campaign in a darkened room lit by candles. Kate’s game character is Glacia the fighter, with strong armor and many weapons; JayJay is Freelik the Frenetic of Glossamir, the cleverest of all sprites; and Robbie is Pardue the holy man, who only uses a sword when his magic fails him.

As time passes, the group continues to play game sessions and Robbie and Kate begin a romance outside the game. Robbie then reveals a personal secret to Kate about his older brother Hall who three years ago borrowed money from him and ran away to New York, to never be seen again. When Robbie and Kate’s relationship begins to take time away from gameplay, JayJay becomes depressed and begins to verbalize half-hearted suicidal ideations and engage in reckless behavior, exploring some nearby boarded-up caves alone.

In a later game session, JayJay’s character Freelik dies. At this point, he proposes a new game, an evolution of Mazes and Monsters he designed. The group will dress as their game characters and act out the gaming sessions in Pequod Caverns that JayJay has mapped out. With JayJay as new Maze Controller, the group enters the caverns where he has set up props such as a skeleton borrowed from the campus science lab. But during the game, Robbie experiences a break from reality and envisions a Gorvil, a dragon-like humanoid, attacking him.

The group ends their game, unaware that in his mind, Robbie has become Pardue. As part of Robbie’s new psyche as Pardue, he becomes celibate and stops seeing Kate romantically. Robbie/Pardue dreams of a hooded character called the Great Hall who instructs him he must find a secret city containing the two towers. Then on the third anniversary of his brother’s disappearance, Robbie/Pardue disappears into the night.

The next day, his friends begin looking for him. After clearing the caves of their game paraphernalia, they report Robbie missing, concealing the fact that they were his M&M co-players. A police detective is quick to pin Robbie’s disappearance on M&M, a large search party is formed to comb the caverns, and we get a repeat of the opening scene. When the police basically give up, the trio look at the materials in Robbie’s dorm room and Kate concludes the Great Hall was not a place but was Robbie’s lost brother.

Meanwhile Robbie wanders New York and has to fend off muggers with his knife and stabs one. In a moment of clarity, he calls Kate and the trio rushes to New York. When they don’t find him, they deduce Robbie/Purdue is headed for the World Trade Center twin towers and prevent him from jumping to his doom.

In the epilogue, the trio of friends drive to visit Robbie three months later at his parent’s upstate ranch after presumed mental health treatment. However, they are disappointed to find him to still be Purdue. They play the game with him one last time.

“We saw nothing but the death of hope and the loss of our friend. And so, we played the game until the sun began to set. And all the monsters were dead.” Roll credits and lame instrumental theme.

Mazes and Monsters aired as a CBS Tuesday Night Movie on Dec 28, 1982 following Bring ‘Em Back Alive. It was on against Gavilan/NBC White Paper on the Reagan Administration on NBC and Threes Company/9 to 5/Hart to Hart on ABC. The broadcast broke into the top 40 in the weekly Nielsens, placing 35th with a 15.6 rating.

Mazes and Monsters was another one of those ‘message’ TV movies. The telefilm gets some aspects of D&D-style role-playing games right, depicting college age nerds bonding over it as both a pastime and creative outlet, but shoehorns in the sensationalized element of costumed live action role playing in nearby dangerous caves and Robbie losing his identity. Just how the characters supposedly ‘worked out’ their real-life problems during gameplay was never explained. How the game itself was supposed to work was also very unclear and inconsistent, especially after gameplay elevated from tabletop to LARPing. The novel and telefilm also allows the reader/viewer to blame Robbie’s break with reality on the influence of the game, instead of his clearly undiagnosed mental illness.

Like the novel on which it was based, production was rapid, which was common for many of these TV movies. Filming was done mostly in Toronto in November 1982. Other productions being filmed that month in the Canadian city included Just the Way You Are (1984) with Kristi McNichol, the Blythe Danner CBS TV movie In Defense of Kids (1983), and classic 80s comedy Strange Brew (1983) with Dave Thomas and Rick Moranis.

As previously mentioned, CBS had picked up the TV movie rights to Rona Jaffe’s novel before it was even released the prior year. Unlike her first experience with having her work adapted, this time she wanted to take a more active role. CBS allowed her to have an associate producer role as well as input on casting. Mazes and Monsters co-producer and sponsor Procter & Gamble were at the time battling an insane, prolific urban legend that postulated they were in league with the devil, which is its own story. A legend about their corporate logo got under way in earnest in early 1980, and by summer of 1982 they were receiving an incredible 15,000 calls and letters monthly from consumers worried their purchase of a box of Tide would support Satanism. Yes, really. 3 I’ve never found proof of this, but their choice to sponsor and co-produce this telefilm had to have been intended as a signal to middle American moms that they, too, shared your concern over the occult and this crazy game the kids were playing.

The novel was adapted into a teleplay by Tom Lazarus, whose best-known credit at the time was likely the 1979 George Burns/Brooke Shields comedy Just You and Me, Kid. The New York City art school dropout would first obtain an entry level position at an ad agency, then move up to managing accounts for small theatrical chains. This led to handling accounts for 20th Century Fox and MCA/Universal. After co-founding a small startup film company with his brother to make educational films, he began writing screenplays which started getting produced first for TV and then film. Following Mazes and Monsters, Lazarus would go on to be executive story editor on Starman and later write late 90s films Air America and Stigmata.

Canadian director Steven Hilliard Stern had started his career with the feature film comedy B.S. I Love You in 1971, which he also wrote. This led to work on a string of salacious TV movies (Anatomy of a Seduction, Portrait of an Escort, Portrait of a Showgirl), followed by the Disney feature The Devil and Max Devlin (1981). The year after Mazes and Monsters, he would helm Still the Beaver, triggering a series revival of 50s/60s favorite Leave it to Beaver. Further notable titles were Disney’s The Undergrads (1985) also with Chris Makepeace, Not Quite Human (1987), and Breaking the Surface: The Greg Louganis Story (1997).

Mazes and Monsters featured (in order of opening credits) Tom Hanks, Wendy Crewson, David Wallace, and Chris Makepeace. The impressive supporting cast included Anne Francis, Vera Miles, Peter Donat, and Murray Hamilton.

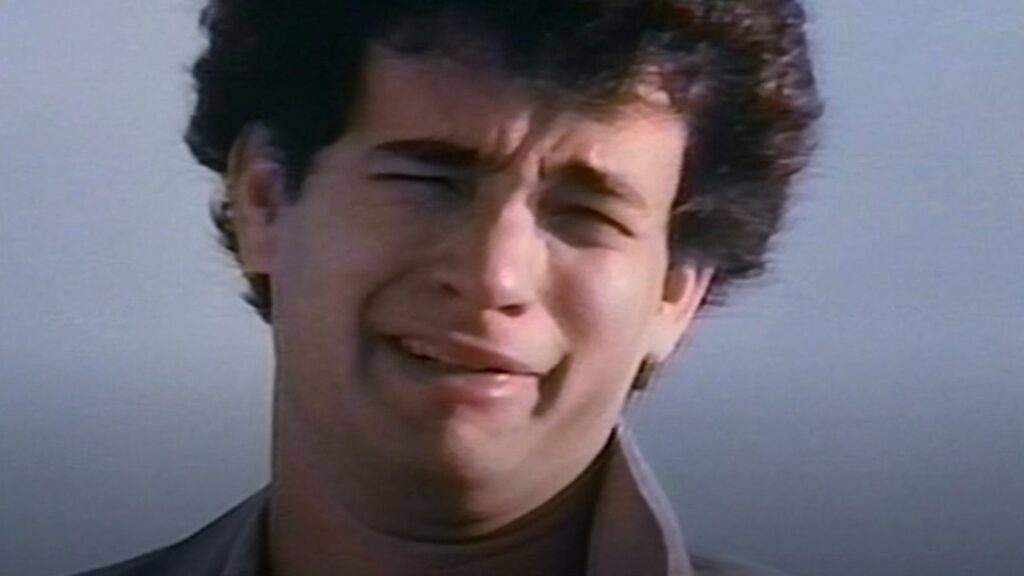

This was an early lead role for Tom Hanks, who needs little introduction being one of the top film stars of the last 40 years. At the time, the 26-year-old Hanks had just finished appearing in ABC’s relatively short-lived Bosom Buddies, one of the last of the Miller-Boyett produced Paramount Television sitcoms. The show gained popularity during the fall season of 1984 in the wake of Tom Hanks screen hit Splash when NBC picked up the broadcast rights and began to rerun it on Saturday nights. Despite its short 37-episode run, it remained popular in afternoon syndication for the rest of the 1980s.

This was one of the earliest roles for the unknown Wendy Crewson, who had been filming Canadian series Home Fires. Mazes and Monsters was her first appearance on US television, and she found the production style different from what she was used to, telling Tom McMahon: “It was a real eye-opener because everything I had done other than that had been for CBC. It’s not that they work better or worse, they just work differently. With Home Fires we work on a lot of rewrites. We improvise a lot and your input is valued.” Crewson found that during production of Mazes and Monsters, her input wasn’t all that welcome when she approached writer and executive producer Rona Jaffe. “She didn’t take very kindly to me telling her some of the lines were too literary and wordy and I really did refrain after that. Well, there was once or twice where I really did have to say something.” 4

Crewson became a regular on one failed American TV series after another for the remainder of the 80s. However, she went on to have quite a career as a working actress; you’ve seen her star alongside Harrison Ford on Air Force One (1997), in the Santa Clause films, on TV series ReGenesis, Saving Hope, and When Hope Calls.

David Wallace (who now goes by David Wysocki), had appeared on telefilms The Babysitter (1980) and Miracle on Ice (1981), as well as episodic television, including an episode of The Powers of Matthew Star that fall. He later enjoyed long stints on Days of Our Lives and General Hospital.

Chris Makepeace had appeared in Meatballs (1979) but began to be noticed after his lead role in My Bodyguard (1980) as a bullied teen who hired his own personal protection in the form of an 18-year-old Adam Baldwin. Makepeace was 18 during filming of Mazes and Monsters, and the young actor bore such a strong resemblance to Dallas Egbert I was surprised he wasn’t given the ‘Robbie’ role.

The ‘Gorvil’ humanoid dragon creature from Robbie’s dreams was played by later 7’2” Predator actor Kevin Peter Hall. Hall had portrayed creatures from horror films Prophecy, Without Warning, and One Dark Knight prior to donning the Gorvil suit for Mazes and Monsters. Robert and Kathie Clark designed the Gorvil after having worked together on Evilspeak (1981) and Deadly Eyes (1982), and next on Cujo (1983). Bob Clark has created creatures for Cocoon, Meet the Applegates, and Starship Troopers, among other films. Kathie Clark worked costume design on 80s video favorites Trancers (1984), The Dungeonmaster (1984), TerrorVision (1986), and Robot Jox (1989). For a time, they also ran a company fabricating full body costumes for sports team mascots and live-action costumed characters.

The overly sappy, sentimental music for Mazes and Monsters including the title song “Friends in this World” was composed by Hagood Hardy, who did several TV movies for CBS around this time. He also worked on Anne of Green Gables and Road to Avonlea. While Hardy’s compositions were fine and appropriate for these other films, the music chosen seemed wildly out of place here, something noted by nearly every person who undertakes a review of this telefilm.

The novel and telefilm of course served to enhance the media hysteria over Dungeons & Dragons, and further promoted the narrative that the game was tied to Dallas Egbert’s disappearance and later suicide. While Jaffe was writing her novel, sales of D&D were going through the roof, with sales of the Basic Set increasing sixfold by the end of 1979, and a second manual for Advanced D&D releasing that year. TSR’s 1979 revenue of $2.3 million quadrupled the following year to $8.7 million.

William Dear would publish his own book on the Dallas Egbert case called The Dungeon Master: The Disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III in 1984.5 For the first time, many of the details of the case were finally revealed, and it was shown that Dallas’ disappearance and later suicide had nothing to do with D&D. However, the book title only served to continue to sensationalize the tragedy. And the actual facts presented in the book were largely ignored by the media, both secular and religious, then firmly in the middle of the persecution of D&D as part of a widespread societal Satanic Panic. D&D hysteria seemed to climax in 1985 when 60 Minutes put out a poorly fact-checked piece on the game.

Mazes and Monsters was rerun by CBS as a weekday movie in August 1984. The following year it went into TV syndication, running on independent stations and cable channels where it ran regularly through 2002. In 1986, it received a Lorimar Home Video VHS release. In 2005, it got picked up for DVD release by bargain bin distributor 905 Entertainment, with cover art that deliberately invoked DaVinci Code vibes with the face of a much older looking Tom Hanks.

The telefilm has also gotten a 40th anniversary limited edition Blu-ray release from Plumeria Pictures. The release features new cover art by Paul Shipper, a commentary track, and booklet, but before you go tracking down this now hard-to-find disc, be aware: While advance release information touted that it would be “presented in HD for the first time anywhere in the world”, upon release buyers report video quality that appears to be standard definition with edge enhancement. Meanwhile, the film can be found streaming on over a dozen platforms, with video quality just as good as what appears on the Blu-ray.

A full consideration of Mazes and Monsters will be coming soon to Forgotten TV, which will include completely fleshed out examinations of the Dallas Egbert case, the Dungeons & Dragons panic, and the Procter & Gamble saga.

Forgotten TV Movies is a column that considers made-for-TV movies of the 70s/80s of various genres. Oh, the places we’ll go and the sights we’ll see.

- Dallas Egbert enters death’s dungeon – Newspapers.com™ ↩︎

- Mazes and Monsters Rona Jaffe interview – Newspapers.com™ ↩︎

- Procter & Gamble Satanic Rumor 1982 – Newspapers.com™ ↩︎

- Wendy Crewson article – Newspapers.com™ ↩︎

- The dungeon master : the disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III : Dear, William : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive ↩︎